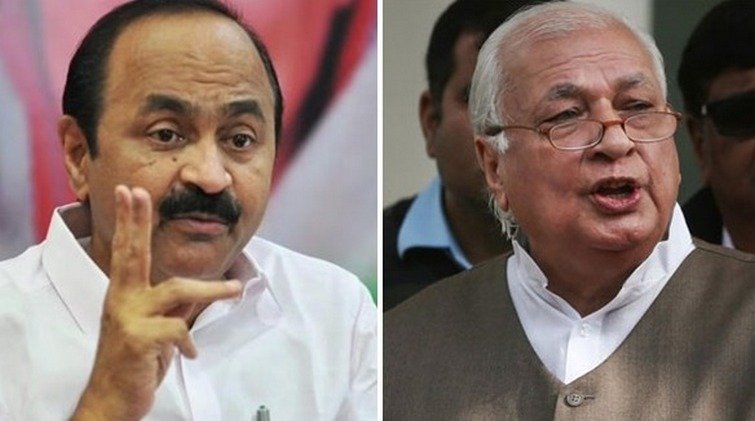

ലോകായുക്ത ഭേദഗതി ഓര്ഡിനന്സില് സര്ക്കാരിന്റെ വാദ മുഖങ്ങള് ഖണ്ഡിച്ച് പ്രതിപക്ഷ നേതാവ് വി.ഡി സതീശന് ഗവര്ണര്ക്ക് വീണ്ടും കത്ത് നല്കി. ഭേദഗതി ഓര്ഡിനന്സ് നിയമ വിരുദ്ധമാണെന്നും ഒപ്പുവയ്ക്കരുതെന്നും ആവശ്യപ്പെട്ട് ജനുവരി 27-ന് യു.ഡി.എഫ് പ്രതിനിധി സംഘം നല്കിയ കത്തില് ഗവര്ണര് സര്ക്കാരിനോട് വിശദീകരണം തേടിയിരുന്നു. ഇതിന് സര്ക്കാര് നല്കിയ വിശദീകരണം തെറ്റിദ്ധരിപ്പിക്കുന്നതാണെന്നു ചൂണ്ടിക്കാട്ടിയുള്ളതാണ് പ്രതിപക്ഷ നേതാവിന്റെ കത്ത്.

പൊതുപ്രവര്ത്തകനോട് ക്വോ വാറന്റോ റിട്ടിലൂടെ സ്ഥാനമൊഴിയണമെന്ന് നിര്ദ്ദേശിക്കാന് കോടതികള്ക്ക് അധികാരമില്ലെന്ന സര്ക്കാര് വാദം തെറ്റാണ്. കെ.സി. ചാണ്ടി Vs ആര് ബാലകൃഷ്ണപിള്ള കേസ് ചൂണ്ടിക്കാട്ടിയാണ് സര്ക്കാര് ഈ വാദമുന്നയിക്കുന്നത്. എന്നാല് രാജ്യത്തെ പരമോന്നത കോടതിയായ സുപ്രീം കോടതി B.R. Kapoor versus State Of Tamil Nadu ( September 21, 2001) എന്ന കേസില് ക്വോ വാറന്റോ റിട്ടിലൂടെ തമിഴ്നാട് മുഖ്യമന്ത്രി സ്ഥാനമൊഴിയണമെന്ന് ഉത്തരവിട്ടിട്ടുണ്ട്. ക്വോ വാറന്റോ റിട്ടിലൂടെ പൊതുപ്രവര്ത്തകനെ ഒരു സ്ഥാനത്ത് നിന്നും പുറത്താക്കാമെന്ന സുപ്രീം കോടതിയുടെ ഈ ഉത്തരവ് രാജ്യത്തെ മറ്റെല്ലാം കോടതികള്ക്കും ബാധകമാണ്.

സര്ക്കാര് വിശദീകരണത്തില് പറയുന്ന കെ.സി. ചാണ്ടി Vs ആര് ബാലകൃഷ്ണപിള്ള കേസില് ഒരു മന്ത്രി നടത്തുന്ന സത്യപ്രതിജ്ഞാ ലംഘനത്തില് ക്വോ വാറന്റോ പുറപ്പെടുവിക്കാനുള്ള പരിമിതി മാത്രമാണ് കേരള ഹൈക്കോടതി ചൂണ്ടിക്കാട്ടിയത്. കേരള നിയമസഭ പാസാക്കിയ നിയമത്തിലൂടെ രൂപീകൃതമായ ലോകയുക്ത അഴിമതിക്കെതിരായ സംവിധാനമാണ്. അല്ലാതെ സത്യപ്രതിജ്ഞാ ലംഘനത്തിനെതിരെ നടപടിയെടുക്കുകയെന്നത് ലോകായുക്തയുടെ പരിധിയില് ഉള്പ്പെടുന്നതല്ല. ലോകായുക്ത നിയമത്തിലെ 14-ാം വകുപ്പനുസരിച്ച് കെ.ടി ജലീല് മന്ത്രി സ്ഥാനത്ത് തുടരാന് യോഗ്യനല്ലെന്ന് ഉത്തരവിട്ടതും ബന്ധു നിയമനത്തിനായി അധികാര ദുര്വിനിയോഗം നടത്തിയെന്ന പരാതിയിലാണെന്നും പ്രതിപക്ഷ നേതാവ് കത്തില് വിശദീകരിക്കുന്നു.

സര്ക്കാര് നല്കിയ വിശദീകരണങ്ങളെല്ലാം ഖണ്ഡിക്കുന്നതാണ് പ്രതിപക്ഷ നേതാവിന്റെ കത്ത്. സര്ക്കാര് നല്കിയ വിശദീകരണങ്ങള്ക്കൊന്നും നിയമത്തിന്റെ പിന്ബലമില്ലാത്ത സാഹചര്യത്തില് ഓര്ഡിനന്സില് ഒപ്പിടരുതെന്ന് ഗവര്ണറോട് പ്രതിപക്ഷ നേതാവ് വീണ്ടും അഭ്യര്ഥിച്ചു.

ഗവര്ണര്ക്ക് നല്കിയ കത്ത് പൂര്ണരൂപത്തില്

This letter is a rejoinder to the government’s response to the UDF letter dated January 27, 2022, which raised legal objections to the proposed Lok Ayukta Ordinance, 2021.

According to media reports, the government has stated that the High Court lacks the authority to declare a public servant unfit for duty through a quo warranto writ. To support its position, the government is said to have cited the Kerala High Court’s decision in K.C. Chandy vs. R. Balakrishna Pillai (AIR 1986 Ker 116).

Kindly note that the government’s contention is founded on incorrect premises. Indeed, the country’s highest court has ruled that the courts have the right to declare a public official unfit for duty via a quo warranto writ. The Supreme Court, in B.R. Kapoor versus State Of Tamil Nadu And Anr, September 21, 2001, issued a quo warranto writ declaring the then-Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu unfit for the position. This Apex Court’s ruling makes it abundantly clear that the Court can declare a public official unfit for duty by issuing a writ of quo warranto. Because the High Court has the authority to consider quo warranto writs under Article 226 of the Constitution, this ruling decision applies to the High Courts of this country as well.

Furthermore, the Kerala High Court’s decision in K.C. Chandy vs. R. Balakrishna Pillai was in relation to the power of the Court to issue a quo warranto for violation of the Oath of Office by a Minister. The contention of the petitioner in K.C. Chandy vs. R. Balakrishna Pillai was related to a public speech alleged to have been made by the Minister on May 25, 1985, which amounted to a breach of the oath taken by him at the time of his assuming the office of the Minister.

The Lok Ayukta is an anti-corruption statutory body and not a body designated to validate the violation of the oath of office. The power has been conferred on the Lok Ayukta by an Act passed by the Legislative Assembly. In the case of Sri K.T. Jaleel, relating to Section 14 of the Act, the Lokayuktha has found him guilty of nepotism and abuse of office to obtain a favour for a relative.

It may be noted that there are other statutes passed by the legislature that declare a public servant unfit to continue in office. Section 8 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, which disqualifies a person convicted of any offence and sentenced to imprisonment for not less than two years from continuing in office, is a prime example.

The government further claims that Section 14 of the Constitutionality of the Lok Ayukta Act has never been subjected to judicial review by the High Court or the Supreme Court.

Please note that the government has previously cited various High Court decisions as the reason for bringing in the proposed ordinance. But, now the government is stating that the constitutionality of the Lok Ayukta Act has not been subjected to judicial scrutiny by the High Court. This clearly shows that the government is dilly-dallying on its stance in order to mislead the Governor and the public.

It would be incorrect to state that Section 14 of the Act was not subjected to judicial scrutiny. In reality, the Supreme Court and the High Court have upheld the Lok Ayukta’s decision, invoking Section 14 of the Lok Ayukta Act in the KT Jaleel case, thereby reinforcing the parent Act’s legal validity.

Another argument advanced by the government to justify the proposed amendment to Section 14 is that it violates Article 164 of the Indian Constitution.

Please take note that Article 13 of the Indian Constitution, which deals with judicial review, states that the state cannot make laws that are not in consonance with the Constitution. The Constitution also empowers the common man to approach the Supreme Court and High Court under Article 32 and 226 respectively when state action or law contravenes the provisions of the Indian Constitution.

The well-established legal principle of ‘Presumption of Constitutionality’ presumes any law made by the Legislature to be constitutional. The Apex Court, on many occasions, has reaffirmed this legal principle, stating that only the Court has the authority to declare a law made by the legislature unconstitutional.

In the Union of India vs Elphinstone Spinning & Weaving case, Justice Pattanaik, in his judgement, has stated thus:

‘After Parliament has said what it intends to say, only the Court may say what Parliament meant to say.None else’.

No Act of Parliament may be struck down because of the understanding or misunderstanding of parliamentary intention by the executive government or because their spokesmen do not bring out relevant circumstances but indulge in empty and self-defeating affidavits. They do not, and they cannot, bind Parliament. Legislation is not to be judged merely by affidavits filed on behalf of the state, but by all the relevant circumstances which the court may ultimately find and, more especially, by what may be gathered from what the legislature has itself said’.

The Supreme Court’s decision makes it very apparent that an executive cannot declare a legislative Act unconstitutional. Only a competent court can. Neither the Supreme Court nor the High Court has ruled that Section 14 of the Act is unconstitutional.

However, in this ordinance, the executive is openly proclaiming a statute that has been in effect for 22 years to be unconstitutional and is proposing an ordinance to change the provision. This is ultra vires and goes against the fundamental tenets of the Indian constitution.

The government’s rebuttal that the proposed amendment does not violate principles of natural justice is based on the wrong premises.

According to the natural justice maxim, Nemo judex in causa sua; no one should be a judge in his or her own cause. After the proposed amendment, the case against the Chief Minister would be decided by the Governor, while the case against the Ministers would be decided by the Chief Minister. Giving the Chief Minister the discretionary power to decide on the fate of a Cabinet colleague appointed by him, and the Governor deciding on the fate of the Chief Minister, is an outright denial of Natural Justice.

The government has also stated that the proposed ordinance does not require the President’s assent.

It should also be noted that the proposed changes to Section 14 of the Act were included in the original legislation when it was introduced in the Legislative Assembly by the then LDF Government in 1999. When the Bill was first introduced in 1999, the aforementioned provisions were part of Section 13 and included a provision that gave the competent authority the authority to reject or accept the Lok Ayukta’s declaration. Members of both the ruling and opposition parties, however, vehemently opposed the provision. The discussion of this section was initially put on hold by E. Chandrasekharan Nair, the then-Law Minister.

After much deliberation and legal scrutiny, an official amendment was brought about by the then Law Minister, removing the contested provision which gave the competent authority the authority to reject the Lok Ayukta’s declaration. The excerpt of the legislative proceeding dated 22.2.1999 containing the reference to the official amendment moved by the then Law Minister is presented as ANNEXURE. As the subject matter is enumerated in the concurrent list, the initial Act has received the President’s assent, and a review of its repugnancy with Central Law is required.

As the proposed ordinance has substantial provisions to water down the eligibility criteria for the appointment of Lokayukta and to provide an executive authority with the power to serve as an appellate authority on a decision by a quasi-judicial decision body, it seems prudent to obtain the assent of the President.

Taking into consideration these contentions, I once again request your good self to abstain from providing your assent to the Lok Ayukta Ordinance, 2021.